In my previous post on the same topic, I related how the Melchizedek Scroll (11Q13) interpreted the passage of Isaiah 61 and it’s proclaiming “liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to those who are bound” in the same manner that Jesus understood it when he proclaimed this passage’s fulfillment in Luke 4. Both the author of the Melchizedek Scroll and Jesus understand these actions to relate to releasing the children of Israel from their sin.

In my previous post on the same topic, I related how the Melchizedek Scroll (11Q13) interpreted the passage of Isaiah 61 and it’s proclaiming “liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to those who are bound” in the same manner that Jesus understood it when he proclaimed this passage’s fulfillment in Luke 4. Both the author of the Melchizedek Scroll and Jesus understand these actions to relate to releasing the children of Israel from their sin.

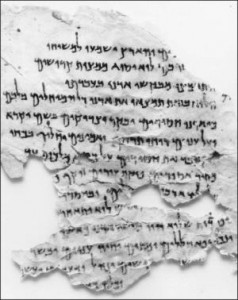

In this post, I would like to continue with another DSS fragment also related to the same passage of Isaiah. It is fragment 4Q521. It is know by a few titles, but I think Geza Vermes’s “A Messianic Apocalypse” is apt enough for our purposes. A correlation between this fragment and Luke 7 has already been made by Martin Abegg, Jr. (Wise, M. O., Abegg, J. M. G., & Cook, E. M. (1996). The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation. HarperOne, p.420.). I would merely like to introduce my readers to this, and expound upon it briefly.

In this passage we find a glimpse into the author’s envisioning of the Messianic redemption of the future where the Messiah will rule, and the reign of God will be over all the earth. The author describes this time as follows:

. . . [the hea]vens and the earth will listen to His Messiah, and none therein will stray from the commandments of the holy ones.

Vermas, Geza (1998). The Dead Sea Scrolls in English. Penguin Books, p. 391.

A brief observation is in order here. During this time, not only will the earth “listen to His [the LORD’s] Messiah, but the heavens as well. The reign of the Messiah during Messianic era is typically limited in scope to either a heavenly realm (as in much of Christian thought), or an earthly realm (as in much of Jewish thought). Here the author proclaims that both the spiritual and physical realms bend their will to the Messiah as they come under his leadership.

A second observation is that the subjects of the Kingdom will obviously have entered into the New Covenant spoken of by the prophet Jeremiah in which God “will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts” (Jeremiah 31:33, ESV). The problem of a unruly heart will have been cured, and we will submit ourselves to His lordship without any deficiency. However, in this text, the commandments of the Torah are said to come from “the holy ones,” rather than purely from God himself. I find this interesting, because it seems to attest to a tradition in the Apostolic Scriptures in which the New Testament authors declare that the Torah was administered by angels. This is too much information to insert here, so I will save this for a subsequent article.

Continuing on with our text, a few lines down we read:

For He will heal the wounded, and revive the dead and bring good news to the poor (Isa. lxi, I).

Ibid., p. 392.

The author links these events (healing the sick, reviving the dead, and bringing good news to the poor) to the time of the Messiah (whether through the Messiah or God himself is unclear), just as we have seen by Jesus. Yet there is something deeper in this text. Let’s take a look at another instance in which Jesus uses the text of Isaiah in a similar manner.

In Luke 7, Jesus is questioned by the disciples of John the Immerser as to whether he is “the one who is to come” or if they should “look for another.” Here is the full context:

And John, calling two of his disciples to him, sent them to the Lord, saying, “Are you the one who is to come, or shall we look for another?” And when the men had come to him, they said, “John the Baptist has sent us to you, saying, ‘Are you the one who is to come, or shall we look for another?'” In that hour he healed many people of diseases and plagues and evil spirits, and on many who were blind he bestowed sight. And he answered them, “Go and tell John what you have seen and heard: the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, and the deaf hear, the dead are raised up, the poor have good news preached to them. And blessed is the one who is not offended by me” (Luke 7:18b-23, ESV).

Again, we see Jesus using this same passage of Isaiah 61 as a prooftext of his Messianic appointment. He speaks to John’s disciples in what Daniel Lancaster terms as a “cryptic answer” (see FFOZ’s Torah Club Volume 4: Chronicles of the Messiah, 2010, Parashat Mishpatim, p. 458.). Rather than coming out and answering the question in direct terms, Jesus, the master of remez, couches his answer in scriptural allusions in order to allow the hearer to make several conclusions at once. But his answer brings us back yet again to Isaiah 61.

Let’s return to the line from the Messianic Apocalypse. The text states that during the time of Messiah, “He will heal the wounded, and revive the dead and bring good news to the poor.” The incredible thing about this is how the author associates the resurrection of the dead with the events of Isaiah 61. Although this concept is never explicitly found in the Hebrew Scriptures, the author of 4Q521 associates the resurrection of the dead with the arrival of the Messiah. This is a rare glimpse into Messianic Jewish expectation of the Second Temple period which offers us a perspective we rarely see in today’s Judaism and its scriptural interpretation, which has been shaped over the last two millennia in reaction to Christian exegesis.

One can only assume that both Jesus and the author of 4Q521 view death as a time of captivity awaiting the final redemption, and interpret Isaiah’s use of “the opening of the prison to those who are bound” as glimpse into the time of this time in which all things will be restored, including life. In the presence of Messiah, not even death can hold his captive securely.

Similar Posts:

- Jesus and the Dead Sea Scrolls, Part 1

- Touching the Leper – Part 2 (of 2)

- Jesus, Friend of Sinners – Part 1

- In Heaven As It Is On Earth?

- Google / IAA Launch Digital Dead Sea Scrolls Online